Cowboy History for Travelers to the U.S. West

The legendary cowboy is part of the American collective identity. But how well do we truly know this almost mythical rider of the American frontier?

Just in time for our family road trip Out West, we’re chucking out cowboy myth and legend and galloping into true American cowboy history. Saddle up and ride along!

Who were the first cowboys?

This question has two answers: a historic account and a linguistic account.

First, for the short one: linguistically speaking, the first cowboys would technically be the first people called “cowboys.” Surprisingly, “cowboy” was originally a derogatory term, referring to Tory (colonists who sided with the British) guerrillas of the Revolutionary War.

Later, during the Civil War, the term was used for Texan boys not old enough to enlist in the Confederate army who then took on the task of tending the family cattle on the home range.

But really, anyone asking the question “who were the first cowboys” is probably looking for the historic discussion of the most beloved stereotyped character of the 19th Century American frontier.

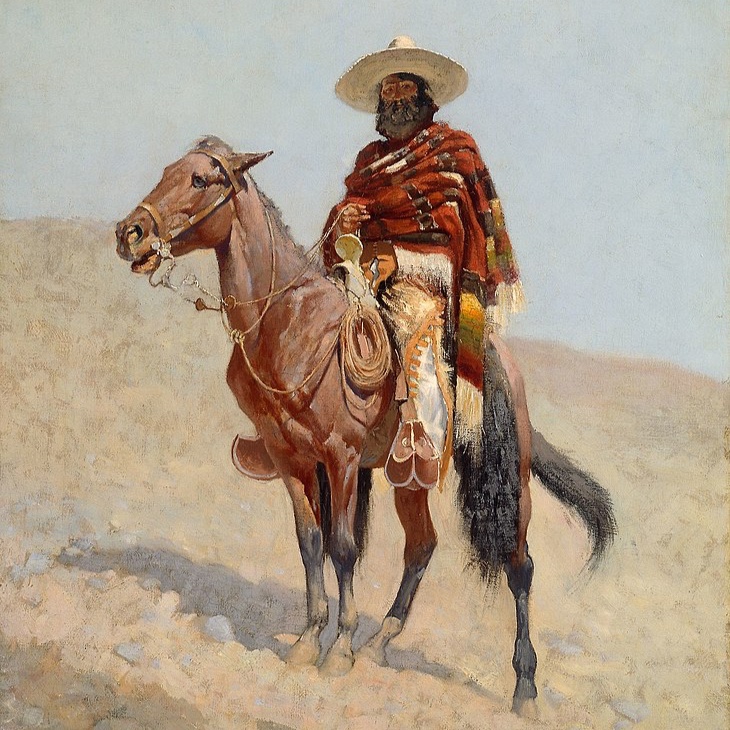

Would it surprise you to know that the first New World cowboys were actually Spanish and Mexican?

Known as “vaqueros” (or “Californios” in Spanish California), these hired hands wrangled herds for the Spanish missions of California, Texas and Mexico as early as the 1500s. Vaqueros established practices that would continue to be used by future cowboys; practices such as free-roaming, castration of bulls, and branding calves with irons to document ownership.

Over time, Spanish and Mexican vaqueros began being assisted by Blacks, Native Americans and Mestizos.

Side Note: Wondering why we use the term Black, not African American? We feel it important to not gloss over the fact that Blacks were denied American citizenship during this era, thus were not African Americans.

“A Mexican Vaquero” by Frederic Remington

Cowboy terms with Spanish origins

buckeroo comes from “vaquero”

lariat comes from “la reata”

chaps comes from “chaparreras”

rodeo is the same word in both languages, and comes from “rodear,” meaning to surround

sombrero is the same word in both languages, and comes from “sombrear,” meaning to shade

We participate in Amazon's affiliate program, which allows sites to earn advertising fees. There is no additional cost to readers making Amazon purchases through our site.

the American cowboy (as we think of him)

The peak era of the stereotyped cowboy began just after the Civil War and ran until the 1890s.

As cattle developed from mere sustenance for a mission, expanding beyond the territory of New Spain, an increasing number of men -and some women- took up work as cowboys.

“The Cow Boy” by John C.H. Grabill.

At the peak of the cattle drive boom, some 40K cowboys worked on the open range, a majority of them white southerners, many former Confederate cavalrymen. The rest: Americans of European descent, European immigrants (primarily poorer Germans and Scandinavians, or rich European adventure seekers), Mexicans, former slaves, and Native Americans. Some were likely running from the law, other seeking adventure, but most were probably just in need of unskilled jobs.

Cowboys were typically hardworking, often seasonal employees who didn’t need to know how to read or write to find employ. They didn’t even need their own horse. Anyone with a saddle, a bedroll and a poncho, plus a willingness to work hard in rough conditions, could likely be hired during round-up and cattle drive seasons.

A Day in the Life of a Cowboy

Round-up season - early spring

Only the wealthiest frontier ranchers owned the land their cattle grazed on. The remaining majority of cattle owners practiced open-range ranching, grazing their stock on public lands, where their cattle would intermingle with other ranchers’ cattle.

Immediately before cattle drive season, a rancher would employ cowboys to round up cattle, separating his from other ranchers’ stock they had been grazing with.

A cowboy’s day during round-up season went something like this:

3:30 am = Breakfast. A typical breakfast might be sowbelly, hot biscuits and coffee.

4:00 am = Rope and saddle horses, then off to round up 3-10K cattle.

Sometime between 9:00 am and 4:00 pm = Dinner was served around the chuck wagon when the last cowboy was in from his morning work (thus the range of times). A rancher would kill one of his beeves and the cook —often nicknamed Miss Sallie or Cookie, despite being a man— would barbecue it. Miss Sallie would also serve pies and coffee for this midday dinner.

Afternoon = Change horses and “cut the herd” (i.e., separate the round-up cattle by owner). Then rope, brand and earmark calves, plus castrate the males.

A chuckwagon on a Texas round-up. U.S. Library of Congress, photographer unable to be found at this time.

6:00 pm = Supper, which could be beef with pinto beans and sorghum molasses, or “son of a bitch stew,” made from leftover cattle parts —bone marrow, heart, testicles, tongue— plus peppers and potatoes.

After supper = Saddle a night horse and get the herd bedded down by 8:00 pm.

Nighttime = Two men at a time guarded the herd. Guard was changed every two hours. Guards typically smoked cigarettes to pass the time and sang to keep the the herd calm.

Cattle drive season - spring to late fall

Once the wild-grazing cattle were separated by brand, and the mavericks (unclaimed stock) were claimed and branded, ranchers determined which of their cattle were ready for sale.

Cowboys then began escorting the stock to a cattle town, where the cattle were loaded onto trains and transported to Kansas City, St. Louis, or Chicago.

A day’s drive was only about 10-15 miles. This allowed cattle sufficient time to graze and hydrate along the way, arriving at their destination in good condition.

On the drive, cowboys slept fully clothed on a bedroll on the ground, surrounded by their lariat (believed to deter snakes), to awaken at dawn and assemble at the chuckwagon.

After breakfast, cowboys saddled up and headed out with the herd. The trail boss rode up front, scouting water holes and grazing options. The chuck wagon followed, along with the spare horses.

Surrounding the cattle were two veteran post men at front; swing men and flank men further back, on either side of the herd. Inexperienced drag riders brought up the rear, prodding stragglers and inhaling dust. Some companies alternated positions at intervals, so that no one ate dust all day.

Besides keeping the herd together, cowboy duties on the drive included: roping and rescuing cattle from quicksand, keeping panicked stock from drowning each other when crossing swollen rivers, doctoring injured stock, hunting predators, and dealing with angry Indians and homesteaders who weren’t excited about thousands of cattle traversing and tearing up their land.

Once a cowboy had delivered his herd to a cattle town for shipment East, he may be ordered to return to the home ranch and get another drove, beginning the long drive again.

“Roundup Scenes” by John C.H. Grabill.

A Cowboy’s Horse

Each cowboy needed up to eight or ten horses for the three- to six-month trail ride. In some cases, horses were provided to a hired cowboy by the rancher; in other cases, a cowboy might have to rope, corral, and break wild mustangs himself. “Bronco busting” (breaking a wild horse to tame it enough to accept a saddle and rider) required five or six days.

Cowboys were expected to keep their horses’ feet in good condition, trimming hooves and shoeing when needed. Many cowboys also thinned out and shortened their horses’ tails, with the result that long-tailed horses became associated with farmers and “town gamblers.”

How a cowboy treated his horse was seen as a measure of the man’s character. Cowboys often came to think of their horses as dear friends; it could be a deadly insult to ride a cowboy’s horse without permission.

Causes of Cowboy Death

The most common cause of death for a cowboy was being dragged by a horse. Pneumonia and tuberculosis also claimed lives, as did being struck by lightning. Fatal shootouts also did occur, but more rarely than depicted in fiction.

Boot Hill Cemetery in Ogallala, Nebraska. Ogallala was Nebraska’s most deadly cowtown, with more fatal shootouts than any other Nebraska city.

Why Cowboys Sang

The plaintive melodies associated with cowboys indicate they sang to express, and maybe even to stave off, loneliness. But cowboys sang for other reasons, too.

Cowboys learned —possibly first by accident— that singing calmed nervous cattle, reducing the risk of stampede. When a nighttime stampede did occur, singing could also help cowboys echolocate one another in the darkness, hopefully helping to avoid circling the stampede right into (or over) one another.

Singing also served the purposes of helping a cowboy stay awake during a night watch, as well as sharing stories within the community.

Cowboys in Cattle Towns

After months on the trail, cowboys arrived at their destinations: cattle towns, where they delivered their stock to be loaded onto trains and shipped East for slaughter.

Following delivery of their charges, cowboys typically headed first for a bath, a haircut, and even a toothbrush - which, in most cases, were wired to a shelf in front of a mirror and used communally.

Next, a cowboy might take some of his roughly $1/day wages and re-outfit himself. Worn boots, hats, and trousers were replaced while in town. Many cowboys commemorated their updated city look with a professional photograph to send home.

Following clean-up, a cowboy might find himself with a bit of left-over money and no work obligations for some period. Free time and money were often spent in saloons, gambling halls, and brothels.

Cowboys in Saloons

A single drink in a saloon could cost a cowboy a dollar (a day’s wage) or more. A common indulgence was a shot of whiskey with a shot of beer -a precursor to the Boilermaker. In Colorado, the mule skinner’s cocktail (recipe coming soon) was popular with cowboys.

If a cowboy declined a drink offered to him, gunfire sometimes ensued. Outside of that context, fistfights were more common than gunfights in saloons.

Some bartenders were willing to run a tab for the duration of a cowboy’s stay in town. Depending on the extent of drinking, payment was sometimes offered in the form of saddles, horses or even acreage.

Cowboys and Gambling Halls

Ranchers typically prohibited cowboys gambling on the range.

Monte, faro and blackjack were popular ways cowboys separated themselves from their money once in town.

Cowboys and Brothels

Beyond the basic services of a brothel, cowboys could also opt for a “cowboy wedding.” This arrangement, complete with a cheap tin wedding ring, would allow a cowboy to spend a week or more with the same prostitute, in a marriage-like situation, including having meals together and -ahem- other marital activities.

The End of the Cowboy Era

By the 1890s, wave after wave of new settlers had arrived in the American West. As these settlers planted crops and began raising sheep, barbed-wire fencing was erected, closing off the open range to cattle drives.

Around the same time, rail lines were extending deeper and deeper into the frontier, making it no longer necessary to drive cattle to railroad termini in far-off cow towns; the railroad had come to the range.

Once cattle drives were no longer feasible (due to fencing) nor necessary (due to rail extensions), the role of the iconic American cowboy greatly diminished on the former frontier. But he lives on in our imagination and collective identity, hopefully for generations to come!

But Cowboys Still Exist!

Working ranches, dude ranches, and guest ranches are great opportunities to experience the modern evolution of the iconic American cowboy. Read all about our visit to Rawah Guest Ranch in northeast Colorado here!

Do you have more cowboy history to add?

We’d love to learn more! Shoot us some facts in the comments below, or share a place you’ve visited that really connected you to this legendary bit of history!

Do you love this nerdy history stuff as much as we do? Then check out:

→ World History through 5 Hot Chocolate Recipes

→ The Story of the American Pie

→ The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center

Or maybe you’re just here for the Westerns? Then don’t miss:

Pin this post for your next trip West!

We participate in Amazon's affiliate program, which allows sites to earn advertising fees. There is no additional cost to readers making Amazon purchases through our site.

Sources: Cattle Kingdom: The Hidden History of the Cowboy West. Knowlton, Christopher. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Co., 2017. Daily Life on the 19th Century American Frontier. Jones, Mary Ellen. Greenwood Press, 1998. Life of the American Frontier. Kallen, Stuart A. Lucent Books, Inc., 1999. Men of the West: Life on the American Frontier. Luchetti, Cathy. W.W.Norton & Company, 2004. The Old West. Hyslop, Stephen G. National Geographic Society, 2015. The Writer’s Guide to Everyday Life in the Wild West, from 1840-1900. Moulton, Candy. Writer’s Digest Books, 1999.